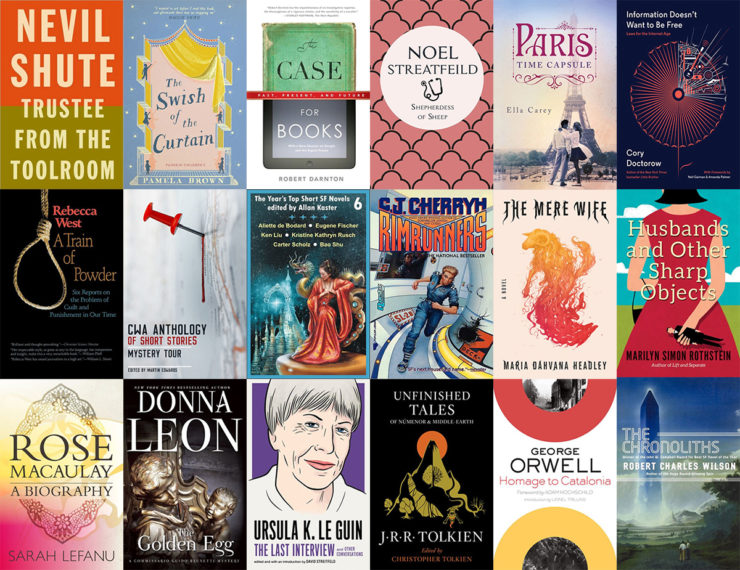

Hi, and welcome to a new regular monthly feature on all the books I’ve read in the last month. I read a whole bunch of things, and a whole bunch of kinds of things, fiction and non-fiction, genre and non-genre, letters, poetry, a mix.

March was a long end-of-winter month here, enlivened with an exciting trip to Hong Kong for Melon Con. I finished 27 books in March, and here they are.

The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Vol I, 1876. Some of the poems in this were great, but some of them were trying to be folk ballads without really having that sense of how ballads work. Having said that, I’m very happy to be reading more of her work than just the amazing Sonnets From the Portuguese and her letters. I can see why she was considered a superstar poet in her own day.

Censors at Work: How States Shaped Literature by Robert Darnton, 2014. I love Robert Darnton. After reading his A Literary Tour de France: The World of Books on the Eve of the French Revolution where he uses the account books of a Swiss publisher and the diary of one of their representatives to trace how publishing worked in detail in France 1794, I rushed off and bought everything else he’d ever written, or at least everything that was available electronically. This one is just as great, and I recommend it thoroughly. The first section is about the censors of the Ancien Régime in France, in the decades before the Revolution, who they were, how they censored, how it worked. The second section is about censorship in British India in the nineteenth century. Then the third section—Darnton was a visiting professor at a university in Berlin in 1989, teaching the French Enlightenment censorship and books, when the Wall came down. And so he got to meet actual real life East German censors, and they talked to him, in detail, about how they had plans for literature and how it all worked. And it’s fascinating and weird and absolutely riveting and filled me with ideas for fiction. Even if the subject wasn’t inherently interesting, which it is, this is the best kind of nonfiction book, full of erudition but written so it can be understood without prior knowledge but without talking down. It’s also written with humour and delight.

Letters of Familiar Matters I-VIII by Francesco Petrarch. (Don’t know how to date these. They were written in the 14th century, but the translation is 1982.) Re-read. Petrarch is famous for writing some love sonnets in Italian to a woman called Laura. But what he really did was kickstart the Renaissance—he came up with the theory that Romans were great and Italians in his own day sucked, and if people found and read the classic Roman books and were educated like Romans, then everything would be all right again, the Middle Ages would be over. He was right. No, really, he was right, the Middle Ages were over! This is the first book of his letters, and they’re lovely, but it includes the ones about the Black Death of 1348, which killed a third of Europe. They are quite traumatic to read. He starts off saying “death is God’s will” but he gets to the point where almost all his friends are dead and he’s saying “Maybe you’re dead too and the only reason I haven’t heard is that there’s nobody left alive to tell me… ” (Boccaccio was, happily, still alive!) and “Why are we being punished like this, are we really so much worse than our fathers’ generation?” Very real letters of a man and a poet alive in 14th century France and Italy.

Buy the Book

Lent

Unfinished Tales of Numenor and Middle Earth by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1980. Re-read. It had been a long time since I read this, and while I enjoyed re-reading it, it did also remind me why I did not enjoy reading all the variant Middle-earth history volumes. “The Tale of Túrin Turambar” here is the best version of that story. It’s a pity he didn’t finish it. It doesn’t seem worth writing about it here at length, because it seems likely that anyone reading this will have already decided whether or not you want to read it.

Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell, 1938. Re-read. Orwell’s memoir of his time in the Spanish Civil War—lucid, illuminating, and written at the white heat of betrayal after he was home but while the Civil War was still going on. I hadn’t read this since I was a teenager, and I know a ton more of the political context, indeed a ton more about all kinds of things, but the experience of reading this book is still the same, to be plunged into the atmosphere of Barcelona in 1936 without due preparation, wanting to make a better world and being stabbed in the back. Deservedly great book.

Rose Macaulay: A Biography by Sarah LeFanu, 2003. LeFanu has written on feminist SF, too. Macaulay was an early 20th century British woman writer, whose book The Towers of Trebizond I read and fixated on at an impressionable age. This is a well-written biography of a strange woman who managed to have an education when that wasn’t the norm, who lived through two world wars, who kept her private life so very private I almost feel I shouldn’t be reading about it even now, and who wrote a bunch of novels and was popular and is now almost forgotten. I recommend this book if any of this sounds at all interesting.

CWA Anthology of Short Stories: Mystery Tour, edited by Martin Edwards, 2017. What it says on the tin, a collection of mystery short stories. Some of them were very good, others less so. Fairly slight overall. Edwards has edited a series of Crime Classic short stories volumes of older mystery stories which I love to pieces, and I was hoping his contemporary anthology would be as good. Not sorry I read it.

Husbands and Other Sharp Objects by Marilyn Simon Rothstein, 2018. I picked this up as a Kindle Daily Deal, the first chapter seemed like I might enjoy it, and hey, $1.99. However as a whole it turned out I didn’t. It did keep my attention sufficiently that I finished it, but… boy, can I find any fainter praise to damn this book with? I am not (as you can probably tell just from reading this far) one of those people who only reads SF and fantasy and says bad things about all mainstream books, but if I were, this would be a very good example of: “Why do people read that when they could be reading about alien invasions?” Not to my taste.

Information Doesn’t Want To Be Free: Laws for the Internet Age by Cory Doctorow, 2014. Fast, interesting, informative. One of the recommended reading books as part of Cory and Ada’s censorship project.

Shepherdess of Sheep by Noel Streatfeild, 1934. Streatfeild wrote a number of highly regarded children’s books, probably most famously Ballet Shoes. Her adult books, which she doesn’t even mention in her autobiography, are also very interesting. Until recently they were either not available or only available very expensively, The arrival of a whole ton of them as ebooks thrilled me to bits. I’ve been reading one a month, because when they’re gone they will be gone. Some of them are very weird indeed. This one is about an unqualified governess who goes into a family where she becomes the most important member and then is eventually discarded. It has problematic treatment of disability—actually very good treatment of physical disability, but terrible treatment of a child with a mental disability. Very strange book, though not the strangest of these.

The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy by Abigail Brundin, 2018. Research. An academic book probably best for those with a serious interest or writing a book that could do with the details. Having said that, this is full of illuminating details, and has a delightful focus on areas of Renaissance Italy that most people don’t look at so much, Naples, the Marche, and the Veneto. And it’s about worship at home, so it has an interesting female focus angle, and it’s looking at all kinds of evidence, not just texts. Enjoyable and useful, but not really for a general reader.

Reginald in Russia and Other Stories by Saki, 1910. Amusing volume of Saki sketches, all very short, mostly very pointed, mostly funny. There’s nothing else quite like them. Warning for period anti-Semitism and racism.

The Case For Books: Past, Present, and Future by Robert Darnton, 2009. (See above re: my newly discovered passion for Darnton.) This is a collection of essays, and thus somewhat disjointed, and somewhat focused on an odd idea Darnton had while at Harvard for the idea of ebooks before ebooks were a thing and when he says “ebooks” he really means odd hypertexts, not books one happens to be reading on an eReader. Somewhat dated. Don’t start here.

The Mere Wife by Maria Dahvana Headley, 2018. A modern retelling of Beowulf that’s really doing something interesting and powerful with the story. Beautifully and poetically written, wrenching in many ways, and making a lot of interesting choices. This is an example of a book that’s great without being fun.

Trustee From the Toolroom by Nevil Shute, 1960. Re-read, and indeed comfort re-read, most of Shute is comfort reading for me. I wrote about this on Goodreads the second I finished it, so let’s just cut and paste:

You know, I love this book with all my heart, it is the story of an ordinary unassuming man going on an unusual trip and winning out because of his ordinary life in which he designs miniature engineering models and people make them. Men, that is, hmm. Anyway, it’s an adorable and unusual book. Read it, you’ll like it, it has SF sensibility without being SF.

But.

It’s 1960. And because of what Shute takes to be the horrible socialist government in Britain, British people cannot legally take all their capital (25,000 pounds, at a time where a house in London costs 2000 and 1000 a year is a reasonable private income) out of the country without being taxed on it. But the characters and the authorial voice, think this is wrong, and do it anyway, and getting it back is a lot of what the book is about. But but but — the reason given, over and over, for getting it back, is so that Janice can have an education. Has it escaped your notice, Mr Shute, that in 1960 if Janice was bright enough to go to Oxford she could have done it without the money? That this was what the taxes were for? So not just lucky Janice but the bright kids who didn’t have a rich parent could go to university? The plot doesn’t work at any other time either—in times of horrible inequality and university out of reach for ordinary people, like the ’30s and oh yes, RIGHT NOW, nobody cares what rich people do with their money, they can turn it into dollars at will, so there’d be no need for it. And yes, it’s great that you see how people who “raised themselves” (in class) by their own efforts are deserving, but you know why we need free education at all levels even for people whose parents didn’t do that is because they’re kids, they’re children, even if their parents are an utter waste these are new people and all of us owe them the future because they’re going to see it and we aren’t.

On the plus side, positive portrayal of non-white characters and Jews. He was really making an effort on that front.

Nevil Shute is dead. I wasn’t even born when he wrote this book. I couldn’t ever have yelled at him about it. And anyway, I genuinely do love it despite the fact that reading it turns me into a raving 1944 settlement socialist.

Also, a classic example of an utterly readable unputdownable book in which nothing happens. Well, I guess there is a shipwreck. But even so.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Conversation and Other Conversations, 2019. A book of interviews with Le Guin, from different points in her life, including one recent “last” one. If I were less familiar with her essays and her work generally, I’d perhaps have found this interesting rather than nostalgic. Death sucks.

The Swish of the Curtain by Pamela Brown, 1941. This is a children’s book I read as a kid but never owned. We used to go on holiday to the same place every year and stay in the same hotel, and they had the same two shelves of books and I’d read them all, and this was one of my favourites there. It’s about three families who live in a street and the children start a theatre company and put on plays and want to go to drama school. It holds up very well to re-reading, if you like books about that kind of thing. There are four sequels, of which I’ve read two (3 and 5) from the wonders of interlibrary loan. They’re being re-released slowly, which is probably just as well, because otherwise I’d have read them all in a non-stop orgy of reading. (I read this the day it came out, throwing over all else.)

Paris Time Capsule by Ella Carey, 2014. Another $1.99 Kindle deal. A girl in New York, with a boyfriend who wants to fix her, inherits a key to a Paris apartment, and with it the apartment, and the mystery of her grandmother’s best friend and why she has it and not the dead friend’s sexy grandson. What happened in 1940? And what will happen now? This has all the ingredients of a deeply predictable but charming romance, and indeed it is that, but the actual answers to the mystery of what happened are sufficiently unsatisfying that I can’t recommend it even as indulgence on a pain day during a blizzard.

Rimrunners by C.J. Cherryh, 1989. Re-read. In fact, this was my reading-in-the-bath book. (My Kindle is supposed to be waterproof, but I don’t want to test it.) Rimrunners is about PTSD, without ever saying it is. It’s also very claustrophobic. It has one space station and one spaceship, and getting off one for the other isn’t the escape one might wish. Great universe, great characters, embedded in the historical context of the series but utterly standing alone so it’s a good place to start. There’s a woman with a mysterious past slowly starving to death on the docks of a station that’s going to be shut down and destroyed. The war is over, except that for some people it’ll never be over. One of my favourites.

The Chronoliths by Robert Charles Wilson, 2001. Re-read. It wasn’t until I was discussing this with friends after this reading that I realised how much this was in some ways a dress rehearsal for Spin (2006). And Spin is so much richer that it can’t help but suffer by comparison. Weird monuments from the future show up claiming victories, and shaping the future they announce. In some ways a variation on a theme of Ian Watson’s “The Very Slow Time Machine.”

The Four Chinese Classics: Tao Te Ching, Analects, Chuang Tzu, Mencius. (Again, the actual date is not the publication date of this 2013 translation.) I’d read the Tao before but not the others, and it was very interesting to read them now, even without as much context as I really needed.

With a Bare Bodkin by Cyril Hare, 1946. Hare is one of the mystery writers I discovered through Martin Edwards’s anthologies of older crime stories, and he’s just great in the cosy Golden Age of Mystery style—complex legal plots, nice neat solutions, fun characters and settings, and he makes me smile too. If you like Golden Age cosies and you’ve read all the obvious ones, Hare is well worth your attention. This one is set at the beginning of WWII among a group of people evacuated to do a job—control pin production—and just as isolated as your country house kind of murder. Delightful.

A Train of Powder by Rebecca West, 1946. Collected essays mostly about the Nuremberg trials and what she imagines they mean for Europe, and the wider context. There’s also an article about a lynching in the U.S., and a treason trial in London, all linked by the theme of justice and society. I love the way West writes. I find her eminently quotable, and even when I don’t agree with her I enjoy the way her mind works. However, unless you’re especially interested in Nuremberg, don’t start here, start with either Black Lamb and Grey Falcon or The Meaning of Treason, because they’re both more coherent books.

Three James Herriott Classics: All Creatures Great and Small, All Things Bright and Beautiful, All Things Wise and Wonderful by James Herriott, 1980. Re-read. These books are collections of anecdotes about being a vet in Yorkshire in the 1930s, and they’re well told anecdotes, well written and as charming now as when I first read them as a kid. But it’s interesting to look at them now in terms of being novels, because each of them has a spine stringing together the vet stories, and the first two work and the third doesn’t. One can learn about story structure from this kind of thing.

What Happened to the Corbetts by Nevil Shute, 1st Jan 1939. Re-read. This book is a historical curiosity. It was written in 1938, and it describes the beginning of an alternate WWII. It’s alternate history now, but it was straight-up SF when he wrote it. It was also very influential in helping persuade the British government to take various actions to do with air raid precautions and sanitation measures to avoid some of what happens in the book. But reading it now… it’s impossible to put one’s knowledge of what really happened sufficiently out of mind not to be filling in the wrong details. There’s a bit towards the end of the book when they go in a yacht to France, and in this reality the equivalent of the Blitz has been doing terrible things to Britain, but France hasn’t been invaded, or even touched… and I got weird whiplash. It’s an odd book indeed.

The Year’s Top Short SF Novels 6, 2016. Actually a collection of novellas, despite the title. The two standouts here were Bao Shu’s What Has Passed Shall In a Kinder Light Appear and Eugene Fischer’s excellent Tiptree Award-winning The New Mother, which I’d read before and which is still great the second time. I can’t get the Bao Shu out of my mind though. It’s a story in which history happens backwards—that is, it starts off set now, with the characters as children, and then goes through their lives with history happening in the background of their lives and sometimes affecting them a lot and sometimes not much, the way history does with people’s lives. But the events that happen are the events of the history of the last 70 years, only in reverse, the Vietnam war preceding the war in Korea which in turn provokes WWII, which is followed by a Japanese invasion of the Chinese mainland and so on—and there’s a focus on China, as that’s where the characters are. I’m amazed anyone could make this work, and it does work. Also, I was thinking about the bewildering succession of collective farms to personal farms and back again, multiple times, when I realised that this was what actually has happened. Only the other way around… the story works. It’s a great story. I was interviewed with him in Hong Kong, and we talked about the similarities it has with my novel My Real Children. Very thought provoking. Tied for best thing I read in March with the Darnton censorship book.

The Golden Egg by Donna Leon, 2013. Ursula Le Guin reviewed one of the Brunetti series. I started reading it at the beginning, and I am rationing these to one a month even though Leon is still alive and still writing. This is volume 22, don’t start here, start with volume 2. These are contemporary mysteries set in Venice, and they’re wonderful and they’re about integrity.

And that’s it. More next time!

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and thirteen novels, including the Hugo and Nebula winning Among Others. Her fourteenth novel, Lent, is coming out from Tor on May 28th 2019. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.